What is Emotional Intelligence?

Emotional Intelligence, or Emotional Quotient (EQ), is an individual’s ability to identify, evaluate, control, and express emotions.

Emotional Intelligence is the ability to reason validly and use emotions to enhance thought.

People with high Emotional Intelligence usually make great leaders and team players because they understand, empathize, and connect with the people around them.

They can manage emotions, use them to facilitate thinking, understand emotional meanings, and perceive others’ emotions accurately.

Emotional Intelligence is a good indicator of workplace success. It is used to identify leaders, good team players, and people who work best alone.

Emotional Intelligence is partially determined by how a person relates to others and maintains Emotional Control.

Self-Awareness Emotional Intelligence

Self-awareness Emotional Intelligence involves self-monitoring our stress, thoughts, emotions, and beliefs, which are essential to Personal Development.

Self-awareness requires deep self-examination, and beware. Honestly, non-judgmental self-analysis isn’t easy.

Increasing self-awareness of false attitudes or inappropriate behaviors requires peace of mind, time, attention, and focus.

Knowing ahead of time that we can change positively through deeper self-awareness makes it worth working on the personal qualities we value most.

But first, we must look within ourselves through self-examination to see what’s there, which is often less obvious than we think.

Self-Regulation Emotional Intelligence

Behaviorally, self-regulation and emotional Intelligence are the ability to act in your long-term best interest and be consistent with your deepest values. Violating one’s deepest values causes guilt, shame, and anxiety, undermining well-being.

Emotionally, self-regulation is the ability to calm yourself down when you’re upset and cheer yourself up when you’re down.

Self-regulation is mainly about controlling your emotions and responses to situations and other people. But it’s also about feeling and expressing positive feelings to others.

Some of the abilities (also known as competencies) that are part of self-management are

- Emotional self-control – controlling impulsive emotions

- Trustworthiness – being honest and taking action that is in line with your values

- Flexibility – being able to adapt and work with different people in different situations

- Optimism – the ability to see opportunities in cases and the good in other people

- Achievement – developing your performance to meet your standards of excellence

- Initiative – taking action when it is necessary

Your ability to self-regulate as an adult has roots in your development during childhood. Learning how to self-regulate is an essential skill that children learn both for emotional maturity and later social connections.

In an ideal situation, a toddler who throws tantrums grows into a child who knows how to tolerate uncomfortable feelings without throwing a fit and later into an adult who can control impulses to act based on painful feelings.

In essence, maturity reflects the ability to face the environment’s emotional, social, and cognitive threats with patience and thoughtfulness.

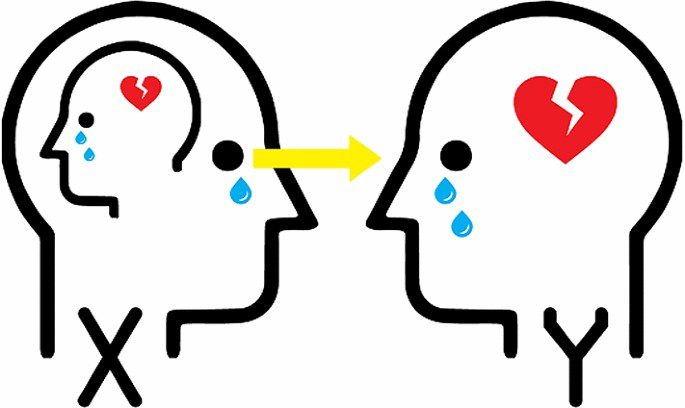

Empathy Emotional Intelligence

Empathy Emotional Intelligence is the visceral experience of another person’s thoughts and feelings from their point of view rather than one’s own.

It’s the ability to imagine ourselves in another person’s shoes, understand their feelings and perspectives, and use that understanding to guide our actions.

Empathy facilitates prosocial or helping behaviors from within rather than being forced, so people behave more compassionately.

Empathy is the ability to cognitively understand a person’s point of view or experience without the emotional overlay, in contrast to sympathy.

Empathy should also be distinguished from compassion, even though the terms are often interchangeable. Compassion is an empathic understanding of a person’s feelings, plus a desire to act on that person’s behalf.

There are differences in empathy between individuals, and there are certain conditions in which empathy is blunted or absent.

Psychopaths are capable of empathic accuracy or correctly inferring thoughts and feelings, but they have no experiential referent: a true psychopath does not feel empathy.

Too much empathy, sometimes known as empathy fatigue or compassion fatigue, can be detrimental to one’s well-being and interfere with rational decision-making. It can cause people to lead with their hearts rather than their heads, lose a broader perspective, or ignore the potential long-term consequences of overly empathic behavior.

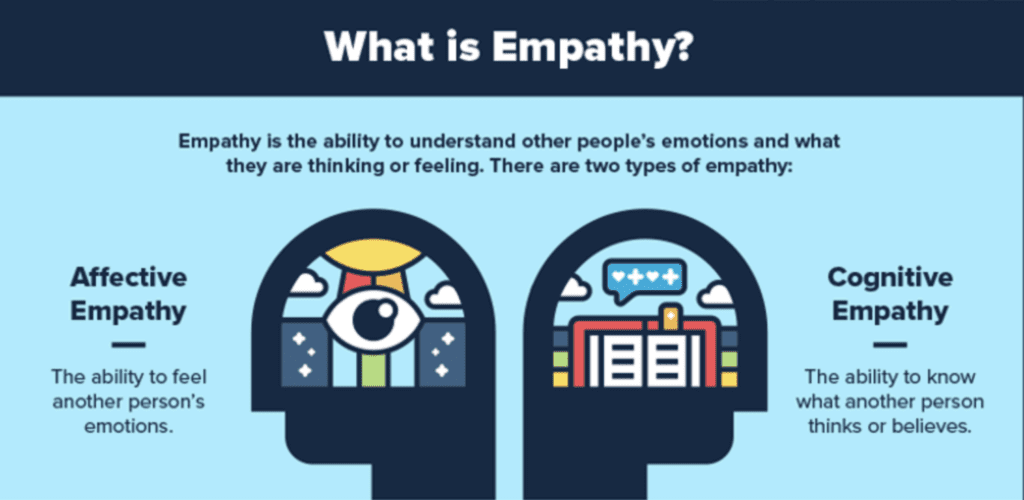

Affective – Emotional Empathy

Affective empathy involves understanding another person’s emotions and responding appropriately. Such emotional understanding may lead to someone feeling concerned for another person’s well-being, or it may lead to feelings of personal distress.

Emotional empathy, also known as ‘personal distress’ or ’emotional contagion,’ is when you feel the other person’s emotions alongside them as if you had ‘caught’ the feelings.

This is closer to the usual understanding of the word ’empathy’ but more emotional.

Emotional empathy can be good because you can readily understand and feel other people’s emotions.

It means that we can respond to others when they are distressed. However, it is possible to become overwhelmed by those emotions and, therefore, unable to respond. This is known as empathy overload.

Those who become overwhelmed need to work on self-regulation, particularly self-control, to manage their emotions better. Good self-control helps doctors and nurses avoid possible burnout from empathizing too much.

There is a danger, however, that they can become ‘hardened’ and not respond appropriately.

Cognitive Empathy

Cognitive empathy involves putting yourself in someone else’s place and seeing their perspective. It also involves understanding another person’s mental state and thoughts in response to the situation.

This relates to what psychologists call the theory of mind, or thinking about what other people think.

Cognitive empathy, also known as ‘perspective-taking,’ is not what most people consider empathy.

Compassionate Empathy

Compassionate empathy is what we usually understand by compassion: feeling someone’s pain and taking action to help.

The name compassionate empathy is consistent with what we usually understand by compassion.

Like sympathy, compassion is about concern for someone, but it also involves action to mitigate the problem.

Compassionate empathy is the type of empathy that is usually most appropriate.

As a general rule, people who want or need your empathy don’t just need you to understand (cognitive empathy). They certainly don’t require you to feel their pain or, worse, to burst into tears alongside them (the emotional heart).

Somatic Empathy

People sometimes physically experience what another person is feeling. Somatic empathy involves a physical reaction to what someone else is experiencing.

For example, when you see someone else feeling embarrassed, you might blush or have an upset stomach. If you see someone hurt, you, too, might feel physical pain.

You can see an echo of somatic empathy, for example, if someone is hit in the stomach with a ball during a sports game and one or two spectators may double over as if they, too, had been shot.

Anecdotally, identical twins sometimes report knowing when the other has been hurt, which might be an example of somatic empathy.

Benefits of Empathy

There are several benefits of being able to experience empathy.

Some of these include:

- Empathy allows people to build social connections with others.

- People can respond appropriately in social situations by understanding what people are thinking and feeling.

- Empathizing with others helps you learn to regulate your emotions.

- Emotional regulation is essential because it allows you to manage your emotions, even during times of great stress, without becoming overwhelmed.

- Empathy promotes helping behaviors.

- You are more likely to engage in helpful behaviors when you feel compassion for others, and others are also more likely to help you when they experience empathy.

What Influences Your Empathy

People don’t experience empathy in every situation. Some people may be more empathetic in general, naturally.

In comparison, depending on the situation, some people can be more or less compassionate toward others.

Some of the different factors that play a role in this tendency include:

- How you perceive the other person.

- How you perceive their behavior.

- How you perceive their predicament.

- Your past experiences and expectations.

At the most basic level, two main factors appear to contribute to the ability to experience empathy: genetics and socialization.

Essentially, it boils down to the age-old relative contributions of nature and nurture.

Parents pass down genes that contribute to your personality, including the propensity toward sympathy, empathy, and compassion.

On the other hand, people are also socialized by their parents, peers, communities, and society.

How people treat others and how they feel about others often reflects the beliefs and values instilled at a young age.

Why People Lack Empathy

Here are a few reasons why people sometimes lack empathy:

They fall victim to cognitive biases

Sometimes, the way people perceive the world is influenced by several cognitive biases.

For example, people often attribute other people’s failures to internal characteristics while blaming their shortcomings on external factors.

These biases can make it difficult to see all the factors contributing to a situation and make it less likely that people will be able to see a problem from another perspective.

People tend to dehumanize victims.

Many also fall into the trap of thinking that people who are different from them don’t feel and behave the same as they do.

This is particularly common in cases when other people are physically distant.

When they watch reports of a disaster or conflict in a foreign land, people might be less likely to feel empathy if they think those suffering fundamentally differ from theirs.

People tend to blame victims.

Sometimes, people blame the victim for their circumstances when another person has suffered a terrible experience.

This is why victims of crimes are often asked what they might have done differently to prevent the crime from happening again. Again, this tendency stems from the need to believe that the world is fair and just.

People want to think that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get — it fools them into thinking that such terrible things could never happen to them.

Balance your Empathy

Cognitive empathy can often be considered under-emotional. This is because it involves terrible feelings and perhaps too much logical analysis. As a result, it may be perceived as an unsympathetic response by those in distress.

Emotional empathy, by contrast, is over-emotional. Too much emotion or feeling can be unhelpful.

Feeling strong emotions, especially distress, takes us back to childhood. More or less, by definition, that makes us less able to cope and certainly less able to think and apply reason to the situation. It is tough to help anyone else if your own emotions overcome you.

In exercising compassionate empathy, we can find the right balance between logic and emotion. We can feel another person’s pain as if it were happening to us and express the appropriate amount of sympathy.

At the same time, we can remain in control of our emotions and apply reason to the situation. This means we can make better decisions and provide appropriate support to them when and where necessary.

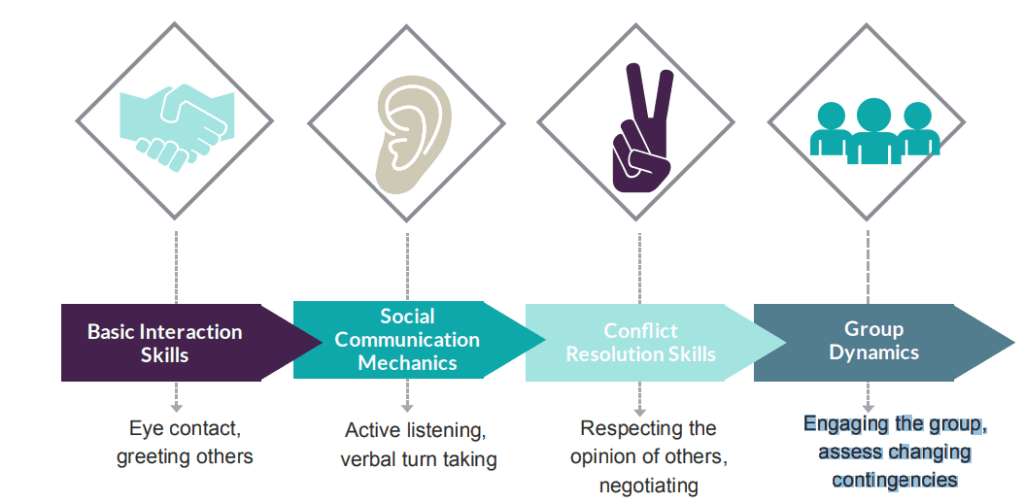

Social Skills Emotional Intelligence

Social Skills Emotional Intelligence is how we communicate and interact with each other, verbally and non-verbally, through gestures, body language, and appearance.

Developing social skills is about being aware of how we communicate with others, the messages we send, and how methods of communication can be improved to make them more efficient and effective.

- Social skills are goal-directed.

- Socially skilled behaviors are interrelated in that one person may use more than one kind of behavior simultaneously for the same goal.

- Social skills should be appropriate for communication.

- Different social skills will be used for professional and personal communication.

- Social skills can be taught, practiced, and learned.

- Social skills should be under the individual’s cognitive control—learning them involves knowing when to use particular behaviors, what behaviors to use, and how to use them.

There are many reasons why a person may have a social skills deficit.

It could occur because of a lack of knowledge, such as the inability to acquire new skills or a competency deficit.

Sometimes, the person may know how to perform the social skill, but they may struggle because of limited practice or inadequate feedback.

Internal or external factors, such as anxiety or chaotic surroundings, may also interfere with the person performing the social skill.

Basic Communication Skills

These include the ability to listen, follow directions, and refrain from speaking.

For example, listening skills involve the ability to concentrate and ignore distractions.

Good listening skills are demonstrated through indicating attention, such as nodding, smiling, and giving feedback on what has been said or discussed.

It also includes the ability to refer to past comments, such as linking a current statement to a previous one or querying potential future ideas, actions, and events.

Basic communication skills include body language and behaviors, like eye contact, physical stillness, and emotional attentiveness while the other person is talking.

Empathy and Rapport Skills

Certain cognitive, behavioral, and mental health conditions may limit an individual’s ability to feel empathy and connect with others.

This includes Autism, documented social impairments, and Borderline Personality Disorder.

Those who suffer from severe social anxiety and those who are highly self-conscious may display too little or too much focus on someone else.

This means that some people with anxiety are desperate to please others and avoid confrontation, so they will pay close attention to what others say or always volunteer to help or do favors.

On the other hand, some people will feel overwhelmed by their social environment and shut down around others.

Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal skills include sharing, joining activities, asking for permission, and waiting for turns.

Those with a social skill deficit may struggle to ask fundamental and concise questions.

Unable to ask a simple question creates barriers to obtaining information and initiating a conversation.

Those who struggle to ask questions will appear disinterested and even anti-social.

Those with poor social skills may prefer to ask closed questions because these elicit brief and controlled responses.

Adults with limited social skills may struggle to understand proper manners in different social contexts and settings.

Problem-Solving Skills

Problem-solving involves asking for help, apologizing to others, deciding what to do, and accepting the consequences.

Some people may struggle to identify the root causes of problems, so they can’t fully understand potential solutions or strategies.

Those who struggle with solving problems may be morbidly shy or clinically introverted.

They may prefer to avoid problems because it makes them feel uncomfortable.

Those who struggle with solving problems will likely have poor conflict-resolution skills.

Some children struggle to appropriately deal with teasing, while some adults have difficulties coping with losing to competition.

Accountability

Some people are petrified of being criticized in public.

They may struggle with accepting blame for problems or dealing with constructive feedback.

Some people naturally associate accountability with reliability and maturity.

Someone who promises to do something and then fails to do it may have a legitimate excuse. Still, their overt lack of accountability may indicate that they are unreliable and immature.

Accountability is also essential in conflict management because recognizing mistakes is an excellent way to indicate a conciliatory and cooperative attitude.

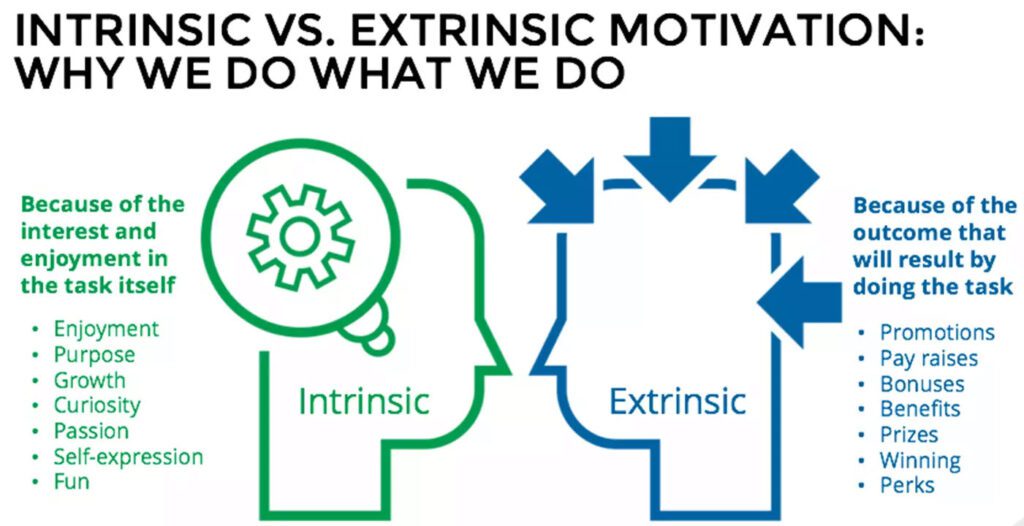

Motivation Emotional Intelligence

Motivation Emotional Intelligence is the desire to act in service of a goal, and it’s crucial in setting and attaining your objectives.

Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic Motivation refers to behavior that is driven by internal rewards.

In other words, the Motivation to engage in conduct arises from within the individual because it naturally satisfies you.

Intrinsic Motivation occurs when we act without any obvious external rewards. For example, we enjoy or see activity as an opportunity to explore, learn, and actualize our potential.

When you pursue an action for the pure enjoyment of it, you are doing so because you are intrinsically motivated. Your motivations for engaging in the behavior arise entirely from within.

Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic Motivation arises from outside the individual and refers to behavior driven by external rewards such as money, fame, grades, and praise.

It occurs when we are motivated to perform a behavior or engage in an activity to earn a reward or avoid punishment.

In this case, you engage in conduct not because you enjoy or find it satisfying but to get something in return or avoid something unpleasant.

Emotional Motivation

Whether subtle or intense, conscious or unconscious, overt or covert, all emotions have one of three motivations:

- Approach

- Avoid

- Attack

Approach Motivation

In approach motivation, you want to get more of something, experience more, discover more, learn more, or appreciate more — you increase the value or worthiness of your attention.

Common Approach Emotions

- Interest

- Enjoyment

- Compassion

- Trust

- Love

Common Approach Behavior

- Learning

- Encouraging

- Relating

- Negotiating

- Cooperating

- Pleasing

- Delighting

- Influencing

- Guiding

- Setting limits

- Protecting

Avoid Motivation

By avoiding Motivation, you want to get away from something—you lower its value or worthiness of your attention.

Common Avoid Behavior

- Ignoring or Dismissing it

- Withdrawing from it

- Rejecting it’s beneath you

Attack Motivation

In attack motivation, you want to devalue, insult, criticize, undermine, harm, coerce, dominate, hinder, or destroy.

Common Attack Emotions

- Anger

- Hatred

- Contempt

- Disgust

Common Attack Behavior

- Demanding

- Manipulating

- Dominating

- Coercing

- Threatening

- Bullying

- Harming

- Abusing