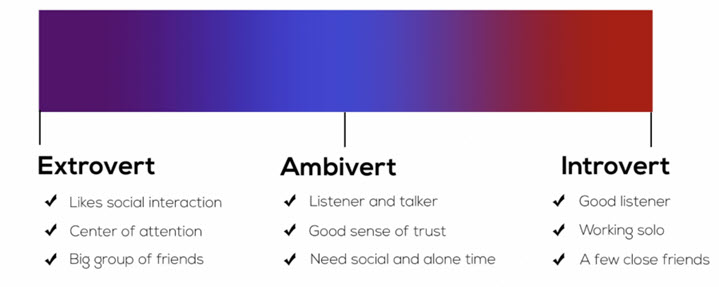

Most people think being Introverted or Extraverted is as simple as falling into one of two boxes:

- Would you rather stay home on a Friday night in your pajamas or go out to the bars with a big group of friends?

- Would you rather be the center of attention or stay as far away from the spotlight as you can?

But the truth is, your personality is not that black and white. Nevertheless, there are some physiological differences between introverts and extraverts.

Dopamine Differences

One significant difference between introverts' and extroverts' brains is how we respond to the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Dopamine is a chemical released in the brain that motivates one to seek external rewards like earning money, climbing the social ladder, attracting a mate, or getting selected for a high-profile project at work.

When dopamine floods the brain, introverts and extraverts become more talkative, alert to their surroundings, and motivated to take risks and explore the environment.

Introverts do not have less dopamine in their brains than extraverts do. Both introverts and extraverts have the same amount of dopamine available.

The difference is in the activity of the dopamine reward network. It is more active in extraverts' brains than in introverts' brains.

Acetylcholine Differences

Introverts prefer to use a different neurotransmitter called acetylcholine,

Like dopamine, acetylcholine is also linked to pleasure; acetylcholine makes us feel good when we turn inward.

It powers our abilities to think deeply, reflects, and focus intensely on just one thing for an extended period.

It also helps explain why introverts like calm environments—it’s easier to turn inward when we’re not attending to external stimulation.

When I lounge at home in quiet solitude, lost in a book or watching Netflix, I’m basking in the pleasant effects of acetylcholine.

Nervous System Differences

Another piece of the introvert-extravert puzzle has to do with the nervous system.

Acetylcholine is linked to the nervous system's parasympathetic side, nicknamed the "throttle down" or "rest-and-digest" side.

When we engage the parasympathetic side, our body conserves energy and withdraws from the outer environment.

As a result, our muscles relax; energy is stored; food is metabolized; pupils constrict to limit incoming light, and our heart rate and blood pressure lower.

Our body gets ready for hibernation and contemplation—two things introverts like the most.

Both introverts and extraverts use both sides of their nervous systems simultaneously, just like they use both neurotransmitters.

But—no big shocker here—extraverts tend to favor the opposite side of the nervous system: the sympathetic side, known as the "full-throttle" or "fight, flight, or freeze" system.

This side mobilizes us to discover new things and makes us active, daring, and curious.

The brain becomes alert and hyper-focused on its surroundings.

Blood sugar and free fatty acids are elevated to give us more energy, and digestion is slowed.

Thinking is reduced, and we become prepared to make snap decisions.

While extraverts thrive on the dopamine-charged good feelings created when they engage the sympathetic side, it's too much for introverts.

Is it Extravert or Extrovert?

A lot of people ask the question, 'What is the correct spelling of the word extravert?

Is it with an "A" as an extravert or an "O" as an extrovert?

The reality is it's okay to use either spelling.

To most people, both versions of the spelling generally mean the same thing, so both are considered equally acceptable.

But we needed to decide which form we would use. The decision was to use the spelling of "extravert."

Why the "A" and not the "O"?

First, from a traditionalist point of view, the term "extraversion" wasn't a part of psychology until Carl Jung introduced it into the lexicon of the science world.

Since Jung introduced extraversion and introversion, Psychology has come a long way towards understanding, doing extensive research on the constructs.

And in most cases, psychologists, especially in technical work, have used the "A" spelling.

For example, contemporary research and test development around the Five-Factor and HEXACO models have consistently used the "A" spelling. That way is generally the psychologically acceptable way of spelling it.

Second, from an etymological perspective, the Online Dictionary of Etymology sheds further light on the "A" by showing that the word "extravert" comes from German Extravert, from extra "outside" + Latin vertere, "to turn."

In Latin, the etymology also shows that "extra" and "intro" mean "out of/outward/outside" and "into/inward/inside."

If Latin and word etymology aren't your things, look at the practical side of the word.

The prefix "extra" is common and often used with other words like extraordinary, extrapolate, extraterrestrial, extravagant, etc.

In the English dictionary, "Extro" appears as a prefix less than ten times, with six variations on "Extroversion."

People often wonder where the "O" came from, and nobody knows.

Some think it's because it sounded better or was more symmetrical with the sound and spelling of introversion.

This drives the purists crazy.

In a Scientific America Article, "The Difference between Extraversion and Extroversion" (2015), psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman indicates that it was just an error by Phyllis Blanchard from a 1918 paper where she not only used an "O" but also redefined the meaning of the constructs.

Regardless of the spelling source, around the 1920s, it became a popular way to spell it.

As the evolution of language continues, it has become a widespread alternative.

In conclusion, we're using "extravert" because it's ultimately the original spelling, how the psychological sciences generally spell it, and we wanted consistency in our work.